Creatine is one of the most popular and effective supplements in bodybuilding and other sports that are in some way related to strength. In food it is found mainly in red meat, eggs and fish. In the following article you will learn everything about the correct intake, the effect and the possible side effects of this supplement.

Occurrence and importance

Creatine is a molecule that is naturally produced in the body. Its structure is primarily composed in the liver from the amino acids L-glycine, L-methionine and L-arginine. However, it is also synthesized in the kidneys and pancreas. Creatine is stored to 90% in the skeletal muscles, since it also primarily unfolds its effect here.

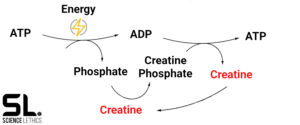

The ultimate energy source of the body is adenosine triphosphate (ATP). This is a molecule of adenosine to which three molecules of phosphate are attached. If we take in energy from food, it must first be converted into ATP before the cells can use it. When the energy from ATP is released, one or two of the phosphate residues are cleaved off, leaving energy-poor adenosine diphosphate (ADP), or adenosine monophosphate (AMP). Creatine, in the form of phosphocreatine, is now responsible for transferring the phosphate residues back to the molecule, thus restoring energy. This rebuilding process is particularly important in the first ten seconds or so of high-intensity exercise until energy supply can be taken over by aerobic and anaerobic energy supply.

Creatine is responsible for regenerating the muscle cell’s ATP supply in the first seconds of a high-intensity activity.

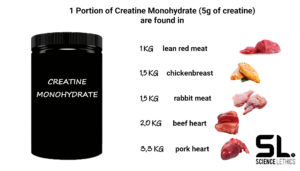

Since this metabolic pathway also occurs in other animals, there are some animal foods that contain creatine.

These include [13, 14]:

- Red meat, free of connective tissue: approximately 5 g/kg.

- Chicken meat: 3.4 g/kg

- Rabbit meat: 3.4 g/kg

- Buffalo heart: 2.5 g/kg

- pork heart: 1.5 g/kg

- liver: 0.2 g/kg

- kidney: 0.23 g/kg

- lung: 0.19 g/kg

- skimmed milk powder: 0,88 %

- blood: 0.04 %

The effect of creatine

Creatine is supplemented primarily for the purpose of improving training performance and muscle building. However, the white substance has a variety of other benefits on the human organism. But let’s start with the obvious.

Muscles and physical performance

Since supplementation increases the content of creatine and phosphocreatin in our muscles, our energy supply improves and we have more strength [1, 2]. This is also the conclusion of numerous scientific studies that have examined the effect of creatine intake on strength development [3, 4, 5]. In the end, more strength means of course more muscle mass, since progression (continuous increase of repetitions and/or weight) is one of the most important factors for the development of further muscle mass.

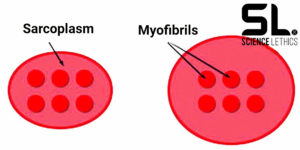

Creatine ingestion causes muscle cells to increase in size due to higher water absorption [15]. This circumstance could decrease the oxidation rate of proteins and thus lead to muscle building independently of protein synthesis [16]. Furthermore, cell swelling affects numerous genes (including PKBa/Akt1, p38 MAPK, and ERK6) in favor of hypertrophy [15].

In addition, a study of 27 healthy men who were initially given 0.3 g/kg creatine for one week and continued to take 0.05 g/kg for another eight weeks showed that, in addition to increasing lean mass and strength, blood myostatin levels decreased [17]. This is a gene that inhibits muscle growth. Animals in which this gene is defective exhibit uncontrolled muscle growth.

Since supplementation increases the creatine content in our muscles, there is normally also an increase in weight. This is because creatine binds water in our muscles and we therefore gain weight. However, due to the higher water content of the muscles, we are also better hydrated at the same time, which can have an influence on performance, especially in summer.

Depression

Studies in humans have shown that creatine is able to reduce depression [6, 7]. While these studies give hope to patients, to date only one of these studies has been free of error and that one used other drugs in addition to creatine. Therefore, no conclusive recommendation can be made at this time.

Cognitive performance

Due to the fact that creatine is only found in animal foods and vegetarians and vegans generally have a lower protein intake, which limits the rate of synthesis from L-arginine, L-glycine, and L-methionine, these groups of people often have lower creatine stores than omnivores. Studies have shown that vegans and vegetarians experience an increase in cognitive performance (memory, learning, and thinking ability) when they take supplemental creatine [18].

In a study of healthy, young subjects that did not consider creatine intake through diet, participants’ fatigue during a math task was reduced. Eight grams of creatine were used over five days [19].

Sleep

Contrary to the myth that creatine intake before bed should lead to a poorer process of falling asleep, studies have found positive influences of creatine on our sleep quality. One study, in which researchers gave participants 20 g of creatine divided into four doses a day before putting them on sleep deprivation for twelve to 36 hours, concluded that supplementation can preserve cognitive performance on complex tasks [20].

Glycogen

Creatine and glycogen appear to be positively correlated, meaning that when one increases in the muscle cell, the level of the other automatically increases as well [21, 22]. Therefore, creatine seems to possess an important role in replenishing the glycogen stores. However, increasing the replenishment of glycogen stores using creatine does not seem to be automatically related to the amount of creatine that enters the cell [23].

Insulin

Although creatine stimulates the secretion of insulin in studies on isolated pancreatic cells, this does not transfer to oral intake in humans [24, 25]. Blood glucose and insulin levels remain unaffected in practice.

Blood flow

In humans, a slight increase in blood flow has been noted with the combination of creatine supplementation and strength training [8, 9]. Thus, one can also expect a slight improvement of the pump effect by taking it, which of course can be enhanced by the additional supplementation of pump supplements.

Testosterone

A three-week study concluded that creatine intake increased dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels without affecting testosterone levels [26]. However, another study showed increased testosterone levels when the white substance was used in combination with strength training [27]. Also, a study on male swimmers showed a 15% increased testosterone level after a six-day loading phase with 20 g creatine daily [28].

The reasons for the different results are not clear. It is possible that testosterone levels are generally raised by creatine, but may be rapidly converted to DHT. Differences in the population of participants used, the methodology of the studies, or the combination with exercise could play a role. However, the literature agrees on one thing and that is that creatine generally slightly raises the level of androgens.

Creatine course – useful or not?

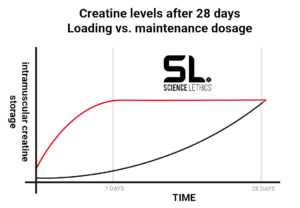

In the past, the supplement was taken almost exclusively in the form of a creatine course. Even today, many people still do a creatine course. But does it really make sense? From our point of view, the answer here is clearly “no!”. Such a course can be accompanied by increased side effects such as diarrhea or nausea, because the quantities taken are very often 20 g to 25 g per day. Although such an approach achieves a faster saturation of the stores, this is also achieved with a little more time with a lower continuous supplementation of about 5 g daily. Creatine must also not be discontinued, but can be taken permanently!

To fill the creatine reservoir to the maximum, you can either use a maintenance dose of 3 to 5 grams per day from the beginning. Thus, the store is slowly filled within a month. To accelerate this process, a 7-day loading phase with 20 grams per day, divided into 4 doses, can also be carried out beforehand.

Creatine intake – the right way!

Generally speaking, an intake of 3 to 5 g of creatine monohydrate per day is recommended. The intake should be done on an empty stomach, otherwise it can happen that the creatine remains longer in the stomach and thus by the stomach acid a larger proportion is converted to creatinine. Creatinine is ineffective for building strength and muscle mass, however, and therefore such a conversion should be avoided.

As long as your cells are saturated with creatine after you load them up, it probably won’t make a difference when you take your creatine. However, a recent study in which 19 exercisers were divided into two groups administered five grams of creatine to one group before training and the same amount to the other group after training. Both groups performed the same workout five days per week over a four-week period.

After one month, the participants who took creatine post-workout had built twice as much lean body mass as the group that took it pre-workout. Also, the first group lost about a kilo more fat mass and bench pressed a few more kilos than the other group. [29]

The researchers believed that the workout may have sensitized the cells regarding creatine uptake, or the post-workout meal may have aided uptake by secreting insulin. No matter what the reason, it can’t hurt to simply take your creatine after your workout and consume it on non-workout days when it’s convenient.

Side effects

Healthy people do not really have to expect side effects when taking normal dosages. For example, one scientific study states the chronic long-term intake of 5 g of creatine monohydrate is safe [10]. In another study, elderly people were given as much as 10 g per day and no meaningful side effects were noted after a total of 310 days [11].

If too much creatine is consumed at once, then diarrhea and other gastrointestinal problems can occur. Some individuals are much more sensitive to this than others. If such side effects occur, then it is recommended that the total dosage be divided into several small doses. The use of micronized (very finely ground) creatine can also help here, as this greatly improves the water solubility of the supplements.

The different creatine variations

As is so often the case, this supplement is also available in capsule or powder form. Whether you should choose creatine capsules or powder is actually obvious. Since the time of intake does not really matter, you rarely or never have to take it with you on the road. Powder, which you take daily at home, is therefore completely sufficient and also has the advantage that it is much cheaper per kilogram of active ingredient than the capsule variant.

What kind of creatine should I take?

Creatine monohydrate is the best studied and most cost-effective form of creatine to date. To date, there is no strong scientific evidence that any other form has advantages over the conventional monohydrate variety.

In the statement of the “International Society of Sports Nutrition” regarding creatine, the authors write [30]:

“The enormous number of studies with positive results of creatine monohydrate supplementation leads us to conclude that it is currently the most effective dietary supplement for increasing capacity for high-intensity training and building lean mass.”

This should make it clear that creatine monohydrate alone would be perfectly sufficient and everything else is just marketing.

In addition to monohydrate, Kre Alkalyn, creatine HCl, creatine AKG and creatine ethyl ester also exist.

In the HCl form is often claimed that this would lead to the same effect at lower doses. However, there is no scientific evidence for this to date.

With the AKG (Alpha Ketoglutarate) form it is assumed that this would lead to a better absorption. Here too, however, scientific evidence is still lacking.

Also with Kre-Alkalyn, a buffered form of creatine, it is claimed that this is better absorbed. According to the current state of knowledge, however, it can be assumed that this is not true!

In general, the various forms are readily used for marketing purposes only appearing to be something newer and better. According to current knowledge, the only thing that makes more sense than taking normal creatine monohydrate, is the micronized version of it (improved water solubility) or Creapure (very high purity).

Conclusion

Creatine is the most effective supplement for increasing capacity for high-intensity training and building lean mass, according to the International Society for Sports Nutrition. It does this primarily by improving energy delivery and thus increasing our strength. It may also have positive effects on health. The supplement does not need to be taken in the form of a course of treatment, but can be supplemented permanently by healthy individuals with a dosage of 5 g per day. Creatine monohydrate is the most effective and inexpensive form of this supplement. Other forms are developed by manufacturers partly only to earn more money with it.

Possibly the most important tool to support your health?

Do you already know our specially designed COMEBACK FITYEAR 2021 Training Programs? 4 dedicated program guides for beginner, as well as intermediate to advanced trainees, who want to become physical active again – at home or at the gym- after a layoff period. We wrote the COMEBACK FITYEAR 2021 Programs, so you can get back in shape – after a break, especially during those pandemic lockdown times. In the comfort of your own home, your own home gym or a commercial fitness club – we got you covered: from solely bodyweight based exercises to simple workout equipment like dumbbells and resistance bands up to a proper gym setup: this is exactly what you need to get a great and effective workout again, while still being able to progress and build muscle!

We are looking forward to your visit on our website. Click here and learn more now.

READY TO TRAIN LIKE A PRO?

LET’S GET YOUR GAINS BACK. TOGETHER.

References

- Del Favero, Serena, et al. “Creatine but not betaine supplementation increases muscle phosphorylcreatine content and strength performance.” Amino Acids 42.6 (2012): 2299-2305.

- Brault, Jeffrey J., et al. “Parallel increases in phosphocreatine and total creatine in human vastus lateralis muscle during creatine supplementation.” International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism 17.6 (2007): 624-634.

- Candow, Darren G., et al. “Effect of different frequencies of creatine supplementation on muscle size and strength in young adults.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 25.7 (2011): 1831-1838.

- Antonio, Jose, and Victoria Ciccone. “The effects of pre versus post workout supplementation of creatine monohydrate on body composition and strength.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 10.1 (2013): 36.

- Arciero, Paul J., et al. “Comparison of creatine ingestion and resistance training on energy expenditure and limb blood flow.” Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental 50.12 (2001): 1429-1434.

- Lyoo, In Kyoon, et al. “A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of oral creatine monohydrate augmentation for enhanced response to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in women with major depressive disorder.” American Journal of Psychiatry 169.9 (2012): 937-945.

- Roitman, Suzana, et al. “Creatine monohydrate in resistant depression: a preliminary study.” Bipolar disorders 9.7 (2007): 754-758.

- Arciero, Paul J., et al. “Comparison of creatine ingestion and resistance training on energy expenditure and limb blood flow.” Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental 50.12 (2001): 1429-1434.

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, Marcos A., et al. “Creatine supplementation attenuates hemodynamic and arterial stiffness responses following an acute bout of isokinetic exercise.” European journal of applied physiology 111.9 (2011): 1965-1971.

- Shao, Andrew, and John N. Hathcock. “Risk assessment for creatine monohydrate.” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 45.3 (2006): 242-251.

- Groeneveld, G. J., et al. “Few adverse effects of long-term creatine supplementation in a placebo-controlled trial.” International journal of sports medicine 26.04 (2005): 307-313.

- Van der Merwe, Johann, Naomi E. Brooks, and Kathryn H. Myburgh. “Three weeks of creatine monohydrate supplementation affects dihydrotestosterone to testosterone ratio in college-aged rugby players.” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 19.5 (2009): 399-404.

- Dahl, Olle. “Estimating protein quality of meat products from the content of typical amino‐acids and creatine.” Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 16.10 (1965): 619-621.

- Harris, R. C., et al. “The concentration of creatine in meat, offal and commercial dog food.” Research in veterinary science 62.1 (1997): 58-62.

- Safdar, Adeel, et al. “Global and targeted gene expression and protein content in skeletal muscle of young men following short-term creatine monohydrate supplementation.” Physiological genomics 32.2 (2008): 219-228.

- Parise, G., et al. “Effects of acute creatine monohydrate supplementation on leucine kinetics and mixed-muscle protein synthesis.” Journal of Applied Physiology 91.3 (2001): 1041-1047.

- Saremi, A., et al. “Effects of oral creatine and resistance training on serum myostatin and GASP-1.” Molecular and cellular endocrinology 317.1-2 (2010): 25-30.

- Lukaszuk, Judith M., et al. “Effect of a defined lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet and oral creatine monohydrate supplementation on plasma creatine concentration.” Journal of strength and conditioning research 19.4 (2005): 735.

- Watanabe, Airi, Nobumasa Kato, and Tadafumi Kato. “Effects of creatine on mental fatigue and cerebral hemoglobin oxygenation.” Neuroscience research 42.4 (2002): 279-285.

- McMorris, Terry, et al. “Effect of creatine supplementation and sleep deprivation, with mild exercise, on cognitive and psychomotor performance, mood state, and plasma concentrations of catecholamines and cortisol.” Psychopharmacology 185.1 (2006): 93-103.

- Low, Sylvia Y., Michael J. Rennie, and Peter M. Taylor. “Modulation of glycogen synthesis in rat skeletal muscle by changes in cell volume.” The Journal of physiology 495.2 (1996): 299-303.

- Robinson, Tristan M., et al. “Role of submaximal exercise in promoting creatine and glycogen accumulation in human skeletal muscle.” Journal of Applied Physiology 87.2 (1999): 598-604.

- Nelson, Arnold G., et al. “Muscle glycogen supercompensation is enhanced by prior creatine supplementation.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 33.7 (2001): 1096-1100.

- Marco, José, et al. “Glucagon‐releasing activity of guanidine compounds in mouse pancreatic islets.” FEBS letters 64.1 (1976): 52-54.

- Green, A. L., et al. “Carbohydrate ingestion augments skeletal muscle creatine accumulation during creatine supplementation in humans.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism 271.5 (1996): E821-E826.

- Van der Merwe, Johann, Naomi E. Brooks, and Kathryn H. Myburgh. “Three weeks of creatine monohydrate supplementation affects dihydrotestosterone to testosterone ratio in college-aged rugby players.” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 19.5 (2009): 399-404.

- Hoffman, Jay R., et al. “Effect of Creatine and β-alanine Supplementation on Performance and Endocrine Responses in Strength/power Athletes.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 38.5 (2006): S126.

- Vatani, D. Sheikholeslami, et al. “The effects of creatine supplementation on performance and hormonal response in amateur swimmers.” Science & Sports 26.5 (2011): 272-277.

- Antonio J, Ciccone V. „The effects of pre versus post workout supplementation of creatine monohydrate on body composition and strength.“ J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2013 Aug 6;10:36.

- Kreider, Richard B., et al. “International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 14.1 (2017): 18.