by Deepika Chowdhury & Rishabh Bhatia

After most of the gyms all over the country have been closed for quite some time now the question arises: what happens if tomorrow there is the possibility to be able to train in the gym again? Because let’s face it, not all of us have, or had the motivation to continue training even without heavy iron and in our own four walls or in the park. But a complete return to training from zero to one hundred after such a long break is certainly not without danger.

Generally speaking, it is entirely possible to continue to make progress or at least maintain the status quo even during the period of studio closures. For the purpose of this article, however, we will assume that the motivation for training in the living room at home with minimal equipment was not particularly high and therefore a complete break was taken. Even if the workout was continued, one’s own body weight and resistance bands do not provide the exact same stimuli and range of motion as the machines and free weights we then have access to again.

Full of renewed motivation, many will go back to the iron to make up for what they have missed and lost over the past few weeks. But as in any sport, sustainability plays a big role if you don’t want to re-injure yourself right away when you get back into training and risk another forced break. Unfortunately, a person’s susceptibility to injury is not only determined by our behavior, but also by our genetics, as recent studies have shown [1]. However, genes and environment have complex interrelationships that are poorly understood to date. In fact, to date, there is no single test that can reliably predict injury [2]. If we look specifically at bodybuilding or powerlifting, injury history is considered the only factor that seems to correlate with occurrence of further injuries in an individual.

Injury prevention is therefore particularly valuable and interesting. Numerous studies have examined this in various sports and the results sound like music to the ears of any strength athlete. For example, one review showed that athletes who perform strength training in addition to their primary sport can reduce injury susceptibility by a full 68 percent, with overuse injuries cut nearly in half [3]. The same group of researchers later demonstrated a dose-dependent relationship between training volume and injury [4]. As a result, increasing training volume by ten percent led to a 4.3 percent reduction in injuries. Strength also appears to have a regulating influence [5]. Stronger individuals therefore seem to have a reduced risk of injury and are able to cope with a higher training volume.

Sounds great, doesn’t it? Full speed ahead for high volume and heavy weights! Not so fast! The problem with interpreting this data is that it looks at the impact of strength training on different sports, not the risk of doing it alone. While the incidence of injuries in powerlifting is quite low, their prevalence in this sport is very high. A survey of Swedish powerlifters indicated that a full 87 percent of respondents had suffered from an injury in the past twelve months, even though the frequency ranged from only one to 4.4 injuries per 1000 hours of training [6, 7].

Thus, the original data seemed promising that we could use changes in training volume to adjust our training to minimize injury [8, 9]. However, more recent data proved this concept to be questionable [10, 11]. All we are saying is that no one can tell us what our injury risk is and we cannot offer a 100% solution that will save you from injury when you get back into training.

Lost muscle mass can be rebuilt faster than new muscle mass

Before we get into how to properly get back into training, we would like to take this opportunity to point out that there is no need to panic and rush things. Unlike muscle mass that your body has never had, lost muscle mass can be rebuilt much faster. The reason for this is the muscle memory effect.

Muscle cells are comparatively large and have multiple nuclei. They represent the switching centers of the cell, which is responsible for protein synthesis, among other things. Due to their size, muscle cells need multiple nuclei to control their entire range. The larger a muscle cell becomes, the more nuclei it needs. To meet this need, satellite cells fuse with muscle cells and donate their nuclei to them. Even if the muscle shrinks due to inactivity, the number of satellite cells remains increased for a very long time, which is also the reason why we quickly rebuild the lost muscle mass after a break in training.

Increase your training volume slowly

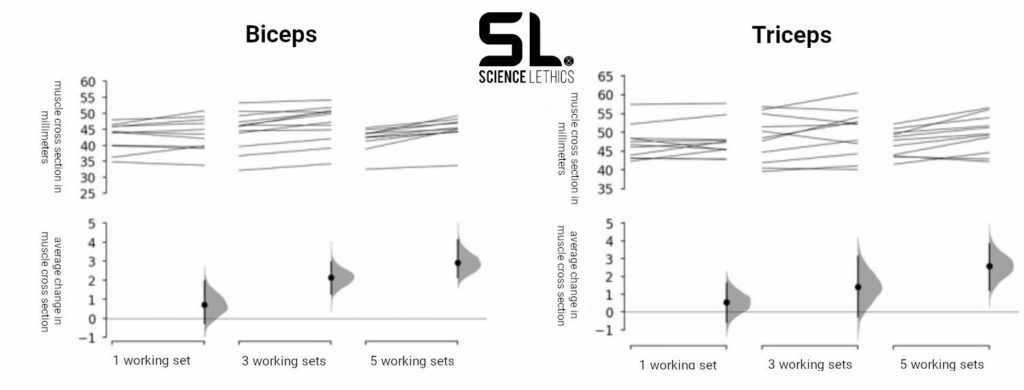

Although the ratio of chronic to acute training volume may not seem like a good benchmark in isolation, it can be helpful in a broader sense. The idea that we shouldn’t drastically increase our training volume is obvious, especially since it seems to be individualized anyway. While a recent study has shown that increasing training volume should be done gradually anyway, it also makes sense in light of the risk of injury to reintroduce slowly [12]. There is evidence that progress in strength and muscle mass is possible with only one set of work per muscle group per training session, although this is not intended to be a universal recommendation at this point [13, 14]. Nevertheless, it demonstrates that we can achieve progress even with a much lower training volume than most probably expect.

The subjects in the study shown in the graph were young, trained athletes who had not previously taken a break. This means that the muscle mass they were building was new and their bodies were used to training at the time. However, thanks to the muscle memory effect, we are able to rebuild the previously acquired muscle mass faster once we get back into training after previously losing it. Therefore, the progress made by a low training volume should be much greater at first.

After a break in training, we should rather underestimate our capacities a bit instead of pushing ourselves beyond the training volume our body can tolerate. When we get back into training, training volume and training intensity (weight in relation to maximum strength) should be almost ridiculously low at first. Increasing both of these factors slowly, rather than risking injury and another break, is the more successful path in the short or long run.

Auto regulate your training

Training programs based on percentages of maximum strength are probably not the best way to get back into training. Even if you’ve trained at home with resistance bands and your own body weight, probably few of us have been able to perform heavy basic exercises. These require not only strength, but also specific neuromuscular coordination. For this reason, the maximum strength you have compared to before the break is now significantly lower, even if you have not lost muscle mass.

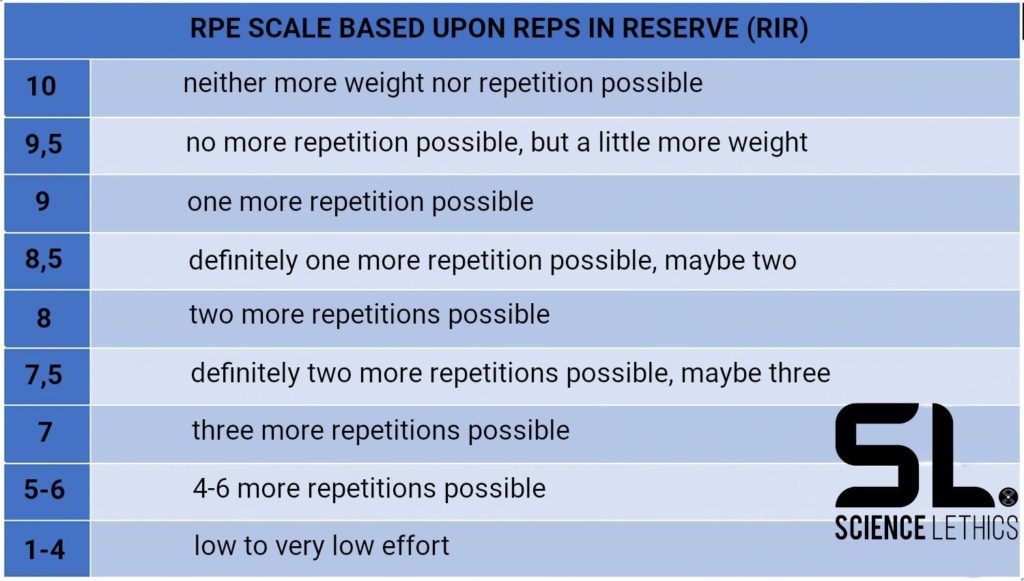

It would also be inadvisable to start training directly with a test of maximum strength, as the risk of injury is particularly high and the rapid progress after re-entry will quickly overtake this value anyway. Instead, try to autoregulate your training. Probably the easiest and also effective way is the RIR scale (Reps in Reserve). This involves subjectively assessing from unit to unit how many repetitions could still be performed before muscle failure occurs in a set [15]. It is a variant of the RPE scale that looks at physiological stress based on subjective sensation (degree of perceived exertion) during a set or over the entire workout.

This scale allows us to adjust the training load in each workout to the level our body is capable of. Most strength athletes have an accuracy of plus/minus one repetition once they are no further than three to five repetitions from muscle failure [16]. Thus, you should be able to stay far enough away from muscle failure and still train hard enough for steady progress to be evident. As advice, we would recommend starting with a moderate number of reps and initially staying two to three reps away from muscle failure in each set when you return to training after rest. This equates to an RIR of 3 and an RPE of 7.

Pay attention to range of motion and speed

The range of motion as well as the speed of motion also has an impact on the risk of injury [17, 18]. These studies suggest that damage to passive structures is related to changes in their length as well as the speed of this extension. When tendons are stretched, they are compressed against surrounding structures. The combination of this compression and stress on the tendon is perceived as particularly damaging. Furthermore, the stress felt by the tendon increases significantly with increasing speed of movement [19].

Of course, this should not prevent you from ever performing a movement explosively and over its full radius. Mild “damage” to tissues provides an important stimulus for positive adaptations [20]. Only if the damage exceeds our ability to recover will we injure ourselves sooner or later. A prolonged break from training alters tissues, reducing their ability to cope with stress. As a result, we should use a slow pace and avoid major stretches under stress initially when we return to training. Suitable options therefore include box squats or floor presses with a slow eccentric (negative) and a controlled concentric (positive) movement.

Do not neglect recovery

To date, there have been no studies that have prospectively examined the impact of sleep duration and quality on injury susceptibility in strength athletes. However, cross-sectional data suggest that good sleep correlates with a reduction in injury susceptibility [21]. But nonetheless, the importance of sleep for muscle development and athletic performance is well established. Although this is certainly not a very exciting topic, since there is not much one can actively do about it except sleep more, it is a very important topic and, moreover, can be optimized without additional financial effort (apart from opportunity costs).

Conclusion and summary

Injuries are complex. They are almost unpredictable and prevention is also difficult. Nevertheless, it is important to avoid them as much as possible when we get back into training so that the next forced break can be avoided. To do this, first start with significantly less weight and training volume than you think you can handle. Leave the ego at the door, or at the latest at the disinfectant dispenser, and demonstrate sanity and reason. Progress can be made even with less volume. When doing so, be careful not to stretch your muscles under load at first and choose a slow execution. Limiting the range of motion can help with this. Furthermore, you should still provide your body with enough sleep and rest to recover from the exertion and make the desired positive adaptations.

Thanks to the muscle memory effect, your muscles will come back quickly, as will strength, even without pushing yourself to your performance limits. Until you are back to where you were before the break, you should gradually increase weight and volume. Although we can’t guarantee that this will keep you injury free, there is little downside to this approach. You control the risk factors you have in hand while generating enough stimulus to quickly catch up to and overtake old times.

You need a proper guidance for your training comeback?

Do you already know our specially designed COMEBACK FITYEAR 2021 Training Programs? 4 dedicated program guides for beginner, as well as intermediate to advanced trainees, who want to become physical active again – at home or at the gym- after a layoff period. We wrote the COMEBACK FITYEAR 2021 Programs, so you can get back in shape – after a break, especially during those pandemic lockdown times. In the comfort of your own home, your own home gym or a commercial fitness club – we got you covered: from solely bodyweight based exercises to simple workout equipment like dumbbells and resistance bands up to a proper gym setup: this is exactly what you need to get a great and effective workout again, while still being able to progress and build muscle!

We are looking forward to your visit on our website. Click here and learn more now.

READY TO TRAIN LIKE A PRO?

LET’S GET YOUR GAINS BACK. TOGETHER.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Primary Source: Jason Eure: “Risks of Returning to Training”, www.strongerbyscience.com

References

- Vaughn, Natalie H., et al. “Genetic factors in tendon injury: a systematic review of the literature.” Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 5.8 (2017): 2325967117724416.

- Bahr, Roald. “Why screening tests to predict injury do not work—and probably never will…: a critical review.” Br J Sports Med 50.13 (2016): 776-780.

- Lauersen, Jeppe Bo, Ditte Marie Bertelsen, and Lars Bo Andersen. “The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” Br J Sports Med 48.11 (2014): 871-877.

- Lauersen, Jeppe Bo, Thor Einar Andersen, and Lars Bo Andersen. “Strength training as superior, dose-dependent and safe prevention of acute and overuse sports injuries: a systematic review, qualitative analysis and meta-analysis.” British journal of sports medicine 52.24 (2018): 1557-1563.

- Malone, Shane, et al. “Can the workload–injury relationship be moderated by improved strength, speed and repeated-sprint qualities?.” Journal of science and medicine in sport 22.1 (2019): 29-34.

- Strömbäck, Edit, et al. “Prevalence and consequences of injuries in powerlifting: A cross-sectional study.” Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 6.5 (2018): 2325967118771016.

- Aasa, Ulrika, et al. “Injuries among weightlifters and powerlifters: a systematic review.” Br J Sports Med 51.4 (2017): 211-219.

- Hulin, Billy T., et al. “Spikes in acute workload are associated with increased injury risk in elite cricket fast bowlers.” Br J Sports Med 48.8 (2014): 708-712.

- Soligard, Torbjørn, et al. “How much is too much?(Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 50.17 (2016): 1030-1041.

- Wang, Chinchin, et al. “Analyzing activity and injury: lessons learned from the acute: chronic workload ratio.” Sports Medicine (2020): 1-12.

- Dalen-Lorentsen, Torstein, et al. “A cherry tree ripe for picking: The relationship between the acute: chronic workload ratio and health problems.” (2020).

- Scarpelli, Maíra C., et al. “Muscle Hypertrophy Response Is Affected by Previous Resistance Training Volume in Trained Individuals.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (2020).

- Androulakis-Korakakis, Patroklos, James P. Fisher, and James Steele. “The Minimum Effective Training Dose Required to Increase 1RM Strength in Resistance-Trained Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sports Medicine (2019): 1-15.

- Schoenfeld, Brad J., et al. “Resistance training volume enhances muscle hypertrophy but not strength in trained men.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise 51.1 (2019): 94.

- Zourdos, Michael C., et al. “Novel resistance training–specific rating of perceived exertion scale measuring repetitions in reserve.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 30.1 (2016): 267-275.

- Hackett, Daniel A., et al. “Accuracy in estimating repetitions to failure during resistance exercise.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 31.8 (2017): 2162-2168.

- Kalkhoven, Judd Tyler, and Mark Langley Watsford. “Mechanical Contributions to Muscle Injury: Implications for Athletic Injury Risk Mitigation.” (2020).

- Cook, Jillianne Leigh, and Craig Purdam. “Is compressive load a factor in the development of tendinopathy?.” Br J Sports Med 46.3 (2012): 163-168.

- Malliaras, Peter, et al. “Patellar tendinopathy: clinical diagnosis, load management, and advice for challenging case presentations.” journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy 45.11 (2015): 887-898.

- Kalkhoven, Judd T., Mark L. Watsford, and Franco M. Impellizzeri. “A conceptual model and detailed framework for stress-related, strain-related, and overuse athletic injury.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport (2020).

- Reichel, Thomas, et al. “Incidence and characteristics of acute and overuse injuries in elite powerlifters.” Cogent Medicine 6.1 (2019): 1588192.